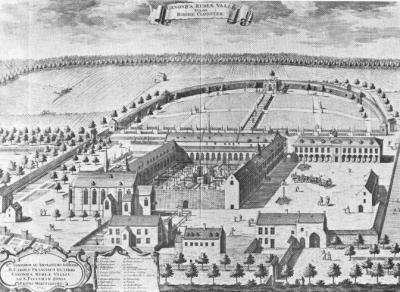

Rooklooster & Its Library CataloguesThe History of Rooklooster in a NutshellRooklooster was one of a number of Augustine priories of Canons Regular to be founded in the late fourteenth century. The origin of the name Rooklooster ("Red Cloister") has been subject to debate, but might be related to the reddish colour of the type of mortar made from ground up tiles that was used to protect the first wooden buildings. Other Rooklooster CataloguesRooklooster boasted an important library and an active scriptorium as a result of the many authors, copiists, miniaturists and binders that worked in the priory. In addition to the Rooklooster Register, some other library catalogues or lists of books originating from Rooklooster have survived to the present day. A list of Middle Dutch books or Dietsche boeke (Brussels, Royal Library, MS. 1351-72), dated to around 1400, has been one of the main sources for a recent study that proves that many fourteenth century Middle Dutch manuscripts, that were kept in the Rooklooster library, were in fact copied by a group of active copiists in the charterhouse of Herne. A bench catalogue from the early sixteenth century (before 1522) has survived (Brussels, Royal Library, MS. II 152), the bibliographical structure of which has many similarities with the Rooklooster Register; it also contains a fragment of an older book list, dating back to 1503. Around the middle of the sixteenth century, a Tabula legendorum in refectorio (Brussels, Royal Library, MS. 242-65) was composed in Rooklooster. Finally, the most recent catalogue of printed works and manuscripts was compiled at the time of the suppression of the priory in 1784 (Brussels, National Archives of Belgium, Comité van de Religiekas - Comité de la Caisse de Religion, Inv. 74/131). Frans Hendrickx Literature

|

|